In search of Urris

I first came across the place name of Urris whilst researching the history of the Gwinnett family. George Gwynedd, his wife, Eleanor and their son Richard arrived in Gloucestershire from Wales in the second half of the 16th century and settled in the Badgeworth area. George was, reputedly, descended from the Princes of Wales and, as such, was obviously reasonably wealthy because, in 1593, he purchased the Manor of Badgeworth, which consisted of the parishes of Badgeworth, Great Shurdington, Little Shurdington, Bentham, Witcombe and Down Hatherley. The family did not set up home in the village of Badgeworth but, instead, settled in Shurdington, where they purchased Crippetts Farmhouse, situated close to the border with Leckhampton.

Fast forward a couple of generations and, in 1651, in the Badgeworth parish registers, was recorded the birth of Elizabeth, the daughter of George and Elizabeth Gwinnett, the great-granddaughter of George and Eleanor. This George, the child Elizabeth’s father, was described as being ‘of Urris’. And there began my search for the location of Urris.

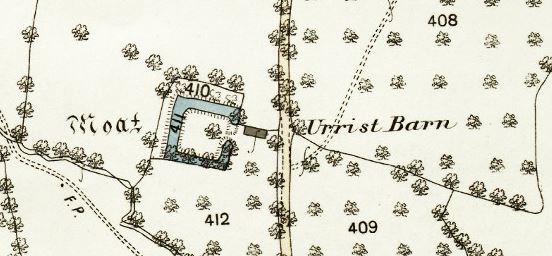

My first search was in the Place-Names of Gloucestershire books by A. H. Smith but Urris was not mentioned there. Nor, unfortunately, does the Victoria County History series cover the Badgeworth area yet. So I resorted to looking at maps and there, on the First Edition of the Ordnance Survey map was Urrist Barn, situated to the south west of the centre of Little Shurdington.

Reproduced from the 1885 Ordnance Survey map with the kind permission of the Ordnance Survey.

This, I thought, had to be the location of Urris that I was seeking. Even more exciting was the drawing of a moat next to the barn. Was this where George lived with his family? A moated house was certainly a possibility for a family of George’s position in society. A visit to the site showed that all that remained of Urrist Barn was a few rocks scattered near to what would have been the entrance to the house; the moat was more or less invisible though I felt I could just see the outline of where it would have been.

I did some more research and found an article in Volume 21 of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society Transactions entitled The Moats or Waterforts of the Vale of the Severn by G. Arthur Cardew, written in 1898 in which he described Urrist Barn Moat. He wrote:

“Near Little Shurdington, is, in my opinion, the most pathetically interesting of all. It is on the western side of a very ancient lane, which is more or less the continuation of the road from Sandford, via Leckhampton, to Shurdington and on to Bentham. There it remains, deserted, uncared for, a picture of desolation, its silence covering probably whole chapters of history never to be read or unfolded. It is the smallest of all I have seen, each face measuring only 50 yards, but having a markedly raised platform. There is no evidence of any house having stood on it.”

On the latter point, he was wrong – there may not have been any physical evidence on site but there had been a house there and evidence of it did exist. When Benjamin Hyett had his many estates surveyed in 1780, Badgeworth was one area included in the book. (G.A Ref: D6/E4). There, by the side of what is now called Dark Lane, was a small drawing of the moat and, within it, shaded pink as were all buildings on the map, was a house. In 1780, the site, No. 56, was called Hook’s Farm. Just outside the moat was another small building, presumably the original Urrist Barn. A few rocks from the latter remain in the field.

Gloucestershire Archives Reference: D6/E4

So this, I assumed, was where George Gwinnett lived with his family. But was it? Searching the Archives’ online catalogue for Gwinnetts, I discovered a collection of deeds for the parish of Badgeworth (Ref: D2957/31) and in there were six documents relating to the Gwinnetts, namely:

- An Enfeoffment of 1631

- A deed of settlement to lead to uses of a Fine, dated 1639

- A marriage settlement of 1646

- An Exemplification of a Fine also dated 1646

- A settlement likewise recorded in 1646 and

- A settlement and counterpart of 1650

Now, when it comes to early land records, I can only describe myself as completely confused! Despite looking up definitions and reading a short booklet on the subject, I really have very limited understanding of what some of these documents are, what they mean and, more to the point, what they can tell me.

Focussing in on the details in the catalogue, for the enfeoffement, I noticed the phrase:

‘Site of the manor of greate Bentham, Badgeworth, commonly called Orrys’

And the description of the settlement of 1646 included the phrase, of:

‘Messuage or site of the manor of greate Bentham Badgeworth commonly called Prris’

So Urris, Urrist, Orris or Orrys (but not the then mis-typed Prris!) was an alternative name for the Manor of Great Bentham. But where was that? I knew where the village of Bentham was but hadn’t been aware of a Manor of Great Bentham within the Manor of Badgeworth or an associated Manor House. So, next, I concentrated on finding more about the Manor of Great Bentham.

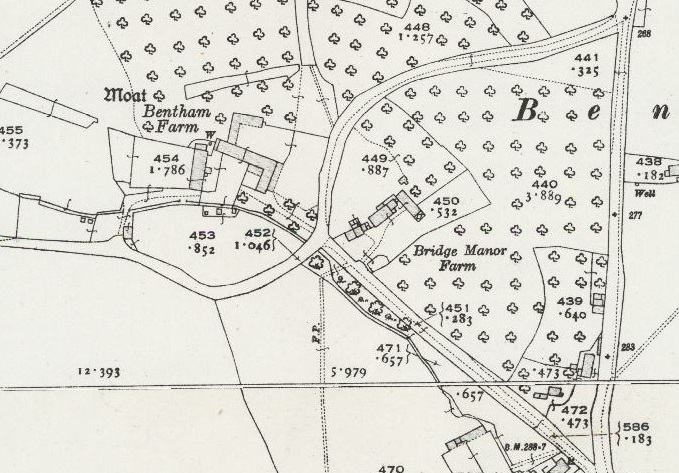

I went back to looking at maps again. None of the O.S. maps actually named Bentham Manor at all, just a Bentham Farm and a Bridge Manor Farm, although, interestingly, the second edition does indicate another moat and buildings at Bentham Farm, just on the opposite side of the lane.

Reproduced from the 2nd edition Ordnance Survey map with the kind permission of the Ordnance Survey.

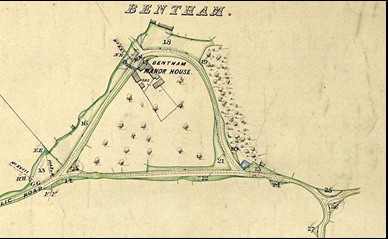

However, the 1871 Inclosure award for Badgeworth included a map which did show an area including Bentham Manor House. Rotate this map through 90 degrees anti-clockwise and the layout of roads looks amazingly similar to that encompassing Bridge Manor Farm on the OS map above. The Inclosure award map did not include the section relating to Bentham Farm.

Gloucestershire Archives Reference: Q/RI/15

So, Bridge House Farm appeared to be the site of the original Bentham Manor House. Had I finally found Urris, the home of George Gwinnett? Then I looked at the Listed Buildings website and there I found further details of Bentham Manor. It described the Manor House thus:

Large house. Possibly C13-C14 (see later) but may be in fact C17 in date. Large blocks of coursed squared and finely dressed limestone, randomly coursed in places; stone slate roof; C20 coursed squared and dressed limestone stacks and 2 brick stacks. Brick and timber framed porch. Rectangular plan with a projecting timber-framed porch. Two storeys and attic. Six-windowed entrance front. C19 two and 3-light casements some with transoms, mostly with horizontal glazing bars, some with leaded panes. Two-light stone-mullioned casement lower right. Three hipped dormers. Central 6-panel door with 2 fielded panels and 2 glazed panels set within a round-headed timber-framed surround. C13-C14 flat- chamfered pointed arch within the porch at the centre of the entrance front. The rear elevation has fenestration similar to that of the entrance front but includes some blocked windows and some single-light windows with flat-chamfered surrounds. Gable-end and axial stacks. It is uncertain whether the C13-C14 archway is in situ, but earthworks to the rear of the house suggest that this house does lie on an early site. Interior not inspected; exterior inspection only possible from the road.

Further down the listing, was the option to download a detailed map but, this time, the label ‘Manor’ was next to the site of Bentham Farm and its moat! Now I was really getting confused! More research was needed. This time, I checked the book Gloucestershire: The Vale and the Forest of Dean by David Verey and Alan Brooks. They state that:

Bentham Manor is probably C17 though with irregular six-bay C19 fenestration; within the central timber-framed porch, a chamfered timber-frame archway, probably ex situ. Almost opposite is Bridge House, C17, stone, though with exposed timber framing at the rear; it has a sweet little C17 dovecote, square, timber-framed with half-hipped stone roof with lantern.

Historic England (No. 1304753) describes the dovecote as follows:

Dovecote three metres north of Bridge House, Bentham, Badgeworth. C17.

Movement of structural timbers on south east and north east walls has caused joints to pull apart, leading to brick panels falling out. Wattle and daub panels are fragmenting. Some timber decay on the west side and cement repairs to the roof are also of concern.

And what about the moat on the Bentham Farm site? I recalled seeing a paragraph in the article by Cardew relating to this moat. He stated:

Bentham Moat has all been drained and mostly filled in. It is possible, however, to trace the old line of the ditch; and Miss Bubb, who resides in the very interesting and quaint old mansion that stands on it, very kindly showed me round and pointed out where it used to be. It was about 100 yards along each face; the angles are not true right angles; and the platform could have been but slightly raised. It is on the Crickly brook, a branch of the Hatherley brook.

Historic England records details of the moat and the nearby fishpond (No. 1016764):

The monument includes the known surviving extent of a moated site and a fishpond. The northern arm of the moat, which is about 90m long, survives to between 6m and 8m in width and up to 1m in depth. The remains of the eastern and western moat arms are visible where they adjoin the northern arm although much of their length has been infilled. That part of them within the area of the scheduling will survive as buried features, but outside the area of the monument they are obscured by later development.

The fishpond to the west of the moat also survives well. Fishponds were of great importance during the medieval period, as they provided a source of protein during the winter months when fresh meat was unavailable. The fishpond, which is about 60m long, has a maximum width of 12m and is between 1.5m and 2m deep. It was fed by a leat from the north west corner of the moat. Although not visible at ground level, buildings are expected to survive as buried features in the unoccupied parts of the island. The ha-ha and all modern fences are excluded from the scheduling, although the ground beneath them is included.

From the various maps, this moat does not seem to have been a basic rectangular shape like the one at Urrist Barn but, presumably it did originally enclose the house itself – why would you build a moat if not to enclose the building within. According to Historic England, the majority of moated sites served as prestigious aristocratic and seigneurial residences with the provision of a moat intended as a status symbol rather than a practical military defence. That certainly fits with my knowledge of the members of the Gwinnett family!

So, I begin to think that Bridge House Farm and Bentham Farm were both part of Bentham Manor with one of the two areas being the site of the main Manor House, probably Bentham Farm, the other property being either the manor farmhouse or another Gwinnett home. And was Urrist Barn also part of the manor, with its neighbouring moated house?

By the mid-17th century, there were four adult sons of George Gwinnett, Lord of the Manor. The eldest, Richard, would have inherited Crippetts farmhouse. There is evidence that the youngest, Lawrence, lived at Poplar Farm on the main road at Great Shurdington. The Manor of Bentham, also called Urris, presumably housed George, the second son. So where did the third son, Isaac, live? Was it in the moated property next to Urris Barn or in Bridge House Farm?

If anyone has any knowledge that can clarify this conundrum, any suggestions of where else I might look for clues, I will be delighted to hear from you.

After G. Arthur Cardew’s article appeared in the Cheltenham Examiner in 1898, there was a response from someone signing himself W.B.C., as follows:

Moats or Waterforts

“Sir – With reference to Mr Cardew’s paper on moats and with special reference to Urrist moat, it might be of interest to some of your readers to know that a man named George Holliday of Bentham who died in 1880, aged 85 or 86, could distinctly remember a small square stone-built house standing in your Urrist Moat, the last occupiers of which were two eccentric brothers named Hook. One of the brothers was drowned in the moat in consequence of a practical joke played on him by the other. It was said that the drowned man was taken in a hearse to Badgeworth to be buried and that from some cause the horses ran away and overturned the hearse and coffin. From this time the moat was said to be haunted and the house gradually fell into ruins. The enclosure was occupied as a garden for several years afterwards.

I remember as a small boy, about 1855-58 when going to school at Little Shurdington to a Mrs Mary Baker, age 95, who by the way always spoke of the French as “the folk who cuts their kings and queens heads off” – myself and brother used to creep up to the side of the moat to see “Old Hook’s Bubbles” which a servant we had told us rose at the spot where he fell in. I expect the said bubbles were caused by frogs. When this girl found we went to see the buckles, she told us “Old Hook had a long stick, and would stretch it out and fetch us in to live at the bottom along of him” – a highly comforting suggestion to two small boys, who used to go quaking and shivering along the lane from Bentham to the dreaded moat was left behind.

It is said that Urrist is a corruption of Hare Hurst the wood or thicket of the hare. Is this so?”

No follow up has been located in response. However, there is definitely a certain amount of truth in his story as the Land Tax records of 1788 and 1789 record a Thomas Hook at Urist.